Pulsus paradoxus, which is a decrease in systolic blood pressure by more than 10 mmHg with inspiration, can also be present in these patients. This triad includes hypotension, jugular venous distention, and muffled heart sounds. When acute pericarditis leads to a clinically significant effusion and cardiac tamponade, Beck’s Triad may be seen. Conversely, tamponade can develop with small effusions if the fluid accumulates over a short period of time.Īcute pericarditis typically presents with ≥ 2 of the following: sharp and pleuritic chest pain that is worse with laying down and improved with leaning forward, pericardial rub, new widespread STE or PR depressions, and new or worsening pericardial effusion. Autoimmune diseases, neoplasms, uremia, and certain infections such as TB can cause large effusions that do not result in tamponade because their slow growth allows the pericardium to stretch and accommodate to the volume of fluid. Whether an effusion leads to cardiac tamponade is determined by both the volume of fluid and the rate of accumulation. The inflammation associated with pericarditis can lead to excess fluid production and the development of an effusion which can ultimately cause hemodynamic instability. Normally, this layer produces ~50 mL of fluid to lubricate the heart and prevent excess motion. She was continued on colchicine for a total of three months and remained asymptomatic on outpatient follow-up visits with cardiology.Īcute pericarditis involves inflammation of the pericardial sac, which is made of an inner mesothelial visceral layer that surrounds the heart. The patient was treated with colchicine (NSAIDs were avoided given her initial presentation of an AKI with history of CKD) and there was no effusion seen on a repeat echocardiogram prior to discharge. Given the patient's clinical history of recent COVID-19 pneumonia and lack of evidence of another infectious process, it was determined that the patient’s pericardial effusion was due to ongoing inflammation from COVID-19. Bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures were all negative. Blood work was significant for potassium of 5.6, creatinine 2.01, WBC 17.3, D-Dimer 948, CRP 240, LDH 324, and troponin 0.6). Her physical examination was significant for conversational dyspnea, diminished breath sounds at the bilateral lung bases, and chronic bilateral lower extremity non-pitting edema. In the ED, her heart rate was 103 bpm, BP 123/67 mmHg, RR 24 breaths/min, temperature 36.7 C, and oxygen saturation 90% on 4L NC with no baseline oxygen requirement. Per medical records from her rehab facility, she did not miss any doses of her anticoagulation. She was recovering from her COVID-19 pneumonia at a subacute rehab facility and had been doing well prior to these symptoms. The patient reported waking up in the middle of the night with left shoulder pain but then developed sudden heaviness in her chest.

#TRIVIAL PERICARDIAL EFFUSION SERIES#

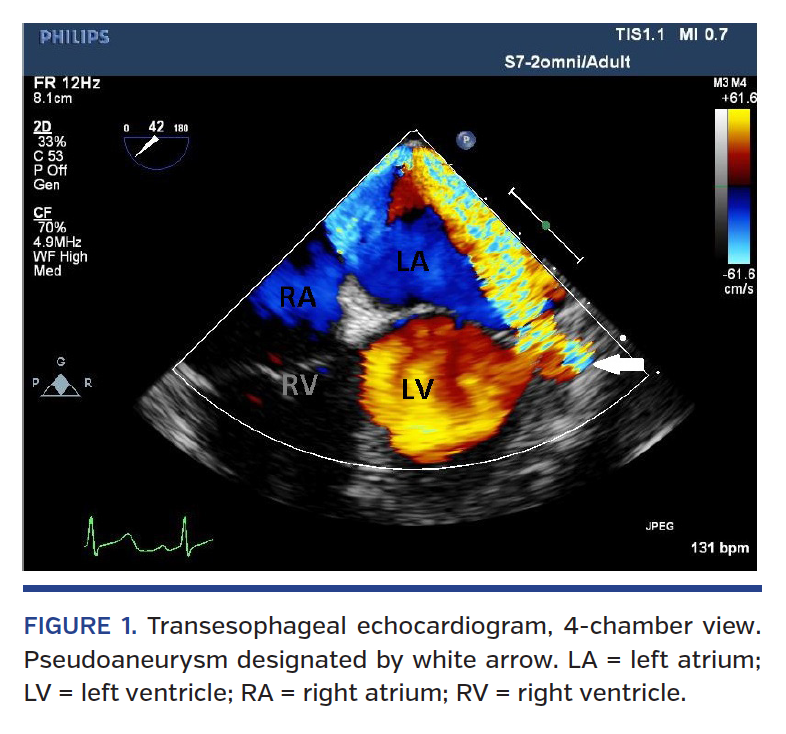

Recently, a series of case reports have described the effect of COVID-19 on myocardial and pericardial tissue.Ī 56-year-old female with a history of CKD, multiple sclerosis, atrial fibrillation, DVT and PE on rivaroxaban, and recently recovered COVID-19 pneumonia presented to the ED due to sudden onset of mid-sternal chest pain that began earlier in the morning.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)